Apollo 17 Oral History Interview Excerpts

|

Eugene

A. Cernan, interviewed 12/11/07

Houston,

the Challenger has landed

At about three meters, you got a contact light,

that little probe hits the surface, tells you you're close,

you better shut the engine down, because if you don't shut

it down and you land with the descent engine running full-blast

at high power, like it was at that point in time, the backpressure

could explode the Lunar Module. So the plan was to shut down

the engine and fall the last nine feet.

As I say, it's very dynamic, very noisy. By the time you get

to 80 feet the ground's quit talking to you, they can't say

much. Long before that, I told Jack [Schmitt], “Don't

talk to me, I don't need the information you're giving me.”

I know he kept calling the fuel out and one thing or another.

By that time I didn't need to hear anything else. When you

shut down and all of a sudden it's like going over a bump

in a country road, you go up, come down, when you shut the

engine down, boom, and you hit. Not real hard, but with a

thump.

That's where you experience the most quiet moment a human

being can experience in his lifetime. There's no vibration.

There's no noise. The ground quit talking. Your partner is

mesmerized. He can't say anything. The dust is gone. It's

a realization, a reality, all of a sudden you have just landed

in another world on another body out there somewhere in the

universe, and what you are seeing is being seen by human beings,

human eyes, for the first time.

Where you are no human beings have ever been before. It's

absolutely—except for the glycol pumps, the environmental

control system fans blowing, which you don't hear—it

is distinctly absolutely 100 percent quiet. From all the activity

and all the dynamics and all the noise and all the talking

and all the vibration it goes to nothing that quick.

It could have been two seconds, ten seconds, a minute or two,

I don't know. But after we all got our breath and realized

hey we are there, that's when I told Houston, “Houston,

the Challenger has landed.” …

And it's

not Earth

When I stepped on the surface, I realized I was really there,

and that for the first time, I'm stepping on another body

in this universe. You can climb the highest mountain or walk

the depths of the deepest ocean on Planet Earth but you're

still on Planet Earth. Now after all that zero-G traveling

for three days and my other flights, I'm standing and touching

something hard, something I can feel, and it's not Earth.

That came home to me very very clearly. I'm living, truly

living in another world at this point in time. There have

been people who want to believe in the fantasy or the conspiracy,

whatever, that it was all done in Hollywood, we never really

walked on the Moon. Well, if they want to have missed one

of the greatest adventures in the history of mankind, that's

their choice. But once my footsteps were on the surface of

the Moon, nobody, but nobody, could ever take, and to this

day can take those footsteps away from me. Like my daughter's

initials I put into the Moon during that three days we were

there. Someone said, “How long will they be there?”

I said, “Forever, however long forever is.” I'm

not sure we, any of us, understand that….

I

saw it with my own eyes

I made the last steps on the 14th. It's the

last steps that are perhaps more memorable to me than that

first step, because I'd been in this valley on the Moon, almost

living in a paradox. Sunshine the whole three days we were

there. Yet surrounded by the blackest black that we can conceive

in our mind, and we don't know how to define it, describe

it. We pull words out like infinity, the endlessness of space,

the endlessness of time, but we don't know what that is. But

I can tell you the endlessness of it all exists, because I

saw it with my own eyes.

So you're in the middle of this. You're part of this unique

part of the universe. Everything's three dimension when you

look back at the Earth in all its splendor, in all its glory,

multicolors of the blues of the oceans and whites of the snow

and the clouds. If your arm were long enough while you're

on the surface, it's almost as if you could reach out and

put it in the palm of your hand and bring it back close to

you and take it home with you. Take it home with you so everybody

else could see.

But when I climbed up the ladder for that last step, and I

looked down, and there was my final footsteps on the surface,

and I knew I wasn't coming back this way again, somebody would—and

somebody will—but I knew I was not going to come back

this way. I looked over my shoulder because the Earth was

on top of the mountains in the southwestern sky. Never moved

for the whole three days we were there.

People kept saying “What are you going to say, what

are going to be the last words on the Moon?” I never

even thought about them until I was crawling up, basically

crawling up the ladder. But I felt as if I'd been on a plateau

somewhere in space.

There

was too much purpose

Science and technology got me to this plateau

on another planet, another body in this universe. Science

and technology got me there, but when I got there and I looked

back home at the Earth, science and technology could not explain

what I was seeing nor what I was feeling. You look at the

Earth, and it very majestically yet mysteriously rotates on

an axis you can't see, but must be there. There are no strings

holding it up. It moves with purpose. It moves with logic.

Every 12 hours you're looking at the other side of the Earth.

It's inconceivable to be somewhere to watch the Earth rotate

in front of your very eyes.

When I looked back home there was too much purpose, too much

logic. The Earth to me—and we all, I think, come home

with our own impressions—was just too beautiful to have

happened by accident. Science and technology could not give

me the answers I was looking for, and I came home with a conclusion

that it's just too beautiful to have happened by accident.

There must be something you and I, all of us don't fully understand

about the creation of the universe, about the miracle of life

itself.

I

wasn't coming this way again

I thought about that, and as I say, it was

a nostalgic moment, because it wasn't like going to Grandma

and Grandpa's farm this summer or for Christmas. You do it

again next year and the next year and the next year. I wasn't

coming this way again. I wasn't coming back. This was it.

I wanted, like in the simulator, I wanted to push the freeze

button, stop time, stop the world. I just wanted to sit there

and think about this moment for a few moments, and hopefully

absorb more subconsciously than I had the ability to take

in consciously. But I couldn't, there was no freeze button.

So up the ladder I went, and that's why my last steps are

probably more memorable to me; although I'd spent a lot of

time almost involuntarily looking at the Earth over my shoulder

the whole time I was on the surface, it was at that moment

that it came home loud and clear that it was uniquely an awesome

and special moment and event in my life. Although we spent

the next night on the Moon in what we call a sleep cycle,

left the next morning, those steps up that ladder, they were

tough to make. I didn't want to go up. I wanted to stay a

while.

Read

Gene Cernan's oral history transcript: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/CernanEA/cernanea.pdf

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Harrison

H. “Jack” Schmitt, interviewed 3/16/00

A

shooting star hit the Moon

Most of the Moon was in Earth shine, not illuminated

by the Sun. I can remember being very impressed by how much

light the Earth cast on the Moon. You could see features very

clearly in this blue light of Earth, and really quite spectacular.

At one point I was looking down at the surface, it would have

been way west of Copernicus, and probably even getting close

to the big basin called Orientale, and I saw a little tiny

pinprick of light on the surface. It was almost certainly

a meteor hitting the surface of the Moon and they will give

off a little bit of visible light. So I had to chance to see

what was effectively a shooting star hit the Moon….

This

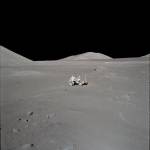

magnificent valley

The first thing I remember is that when I

stepped down from the ladder my—I think it was my left

foot first—got

on the side of a rock with these little beads of glass on

it, and slipped. I can remember hanging onto the ladder while

my foot was slipping off to the side. But those first steps

on the Moon were in the shadow, because that's the way we

had landed, the sun was behind us. Fact is, I would say the

first half hour, forty-five minutes was. You were still in

a very familiar place, even though you were walking and had

the Moon soil beneath you, you were working with the lunar

module, something you had worked with before, and many, many

times, and was like being in the same familiar scene. You

didn't really have a chance to look around you very much.

At least I didn't.

It wasn't until the flight plan called for me to go some seventy-five

meters away from the lunar module in three different points

around it and take a panorama at those three points to document

the site before we had really screwed it up, that's the first

time I had a chance to see this magnificent valley that we

were in, a valley deeper than the Grand Canyon, 7,000 feet,

6 to 7,000-foot mountains on either side, 35 miles long, and

about 4 miles wide where we had landed. The slopes of the

valley walls were brilliantly illuminated by this little Sun,

by that time probably a 10-degree Sun, something like that.

The Sun itself was brighter than any Sun that I had ever seen,

of course, in New Mexico or anywhere else, in a desert-like

landscape.

But most hard, I think, to get used to was a black sky, an

absolutely black sky. The biggest problem I think photographers

have in printing pictures from space is actually finding a

way to print black, absolute black. Certainly slides that

you show will have a little bit of blue in that background,

and you're just never going to get the contrast that we had

visually on the Moon, because the sky was black.

Then hanging over the southwestern wall of the valley was

the Earth, at this point about a two-thirds Earth, in terms

of its phase. The whole scene was really spectacular. It's

one of those things that you have to go see yourself….

And

that's discovery

It was the most highly varied

site of any of the Apollo sites. It was specifically picked

to be that. We had three-dimensions to look at with the mountains,

to sample. You had the Mare basalts in the floor and the highlands

in the mountain walls. We also had this apparent young volcanic

material that had been seen on the photographs and wasn't

immediate obvious, but ultimately we found in the form of

the orange soil at Shorty Crater.

But as soon as you had a chance to look around, you could

tell, everything we expected to find there, and more, was

going to be available to us, and that's what geologists like.

And they really like to have the unexpected. I mean, it's

one thing, part of your jollies are gotten by trying to anticipate

everything you could possibly anticipate, but then you get

a new surge of adrenaline when you find there are things that

you never could have anticipated. And that's discovery. That's

when science really becomes exciting, those things that you

didn't anticipate and they occur, and that's where scientific

discoveries are made. That's the extension of your anticipation….

We found the oldest rock that's been sampled on the Moon at

the base of the South Massif. We found the orange soil, which

is really stirring things up this day and age, because it

makes it very difficult to explain how the Moon might have

formed by a giant impact of a Mars-sized asteroid on the Earth.

The consensus of the scientists is still trying to make that

giant impact work, but I frankly don't think it's going to

work over the long haul. I think we're going to have to have

a different theory than that. The orange soil is right in

the middle of that debate.

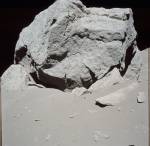

Then the big boulder we worked at at Station 6 was at the

base of the North Massif, was the first time that anybody

had had a chance to see a large exposure of the kinds of materials

that are produced by one of these huge basin-forming impacts

on the Moon, impacts that happened about fifty times on the

Moon and almost certainly happened three or four times that

number on the Earth during the same period. It also was a

period in which life was trying to get started on the Earth,

but didn't get started, as far as we know, until that period

of impact, big-basin forming, was over, about 3.8 billion

years ago.

Two

major benefits to humankind

We were looking at an awful lot of information, not only about

the origin of the Moon, but that was relevant to a better

understanding of the evolution of the Earth, the origin of

the Earth and its evolution, particularly in that period of

time when life was trying to get started here.

Apollo had really two major benefits to humankind.

One is, it demonstrated that free men and women, when faced

with a challenge, can meet that challenge and succeed in a

political and technological race that had a lot to do with

the preservation of freedom on this planet. Secondly, something

that was recognized by George Low and Bob Gilruth and Gene

Kranz and Chris Kraft and Sam Phillips at Headquarters, even

years, several years before Apollo 11, we had the capability

and they allowed us to use that capability to understand the

Moon to a first order scientifically. And that is contributing

in many, many ways to a better understanding of the Earth,

and one never knows all the things that are going to come

from that.

One of the things we didn't know was going to come from that

until fifteen years after we had collected the samples, was

that on the Moon, particularly Apollo 17 and Apollo 11 sites,

we have an energy resource that should be examined very, very

carefully as a future alternative for fossil fuels. That is

a potential return from the expenditure of the taxpayers'

money that nobody could have anticipated, but it is in the

same class of those unanticipated returns that came from Lewis

and Clark exploring the Louisiana Purchase and really has

always come from any type of human exploration that we've

undertaken.

Read

Jack Schmitt's oral history transcript: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/SchmittHH/schmitthh.pdf

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Joseph

P. Allen, interviewed 1/28/03

A

victory of the human organization, dedication, and spirit

A fond observation I have—fond to me,

at least—is there are some great things, great monuments

on planet Earth. One is the pyramids. We’re not sure

what they are monuments to, but they represent the collective

effort of, clearly, tens of thousands of people. Now, it was

probably the physical effort of most of them, but some mental

effort of a few. One doesn’t know.

In

my mind, the Apollo Program in its entirety is a monument

of the same magnitude and beyond, and it represents the collective

efforts of hundreds of thousands of people. These efforts

are the aggregate of virtually every bit of human skill and

knowledge in one way or another, all the way from knowledge

of mathematics that had to do with the trajectory, to the

knowledge of sewing that had to do with the putting together

of the spacesuits. These bits and pieces of knowledge, processes,

techniques, technologies, are across the entire spectrum of

the human intellect, and they were all combined to accomplish

Apollo.

I think that is just extraordinary. I mean, I’m now

reflecting upon a truly heroic effort on the part of a lot

of people, including even the generosity of the American taxpayer.

Virtually everybody in this nation celebrated that, I think,

that effort as a victory. To my mind, it was a victory of

the human organization, dedication, and the human spirit.

As great an accomplishment Apollo was, it was nonetheless

quite different. You know, there were victories of exploration

from earlier times, and there are names associated with them—Christopher

Columbus, Ferdinand Magellan. And these are obviously brave,

perhaps even foolhardy daredevils who attempted and did something.

But, when it came to Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo, they are

no longer an individual person’s name, because the accomplishments

were an aggregate of human effort. To me, that makes the achievement

even more remarkable.

Read

Joe Allen's oral history transcripts: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/AllenJP/allenjp.pdf

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Michael

B. Duke, interviewed 10/13/99

An emotional kind of event

Throughout the Apollo Program and in most NASA programs, the

engineers are in charge. The engineers are the ones that make

the systems work, and they really have to look carefully at

every little angle that is important to the mission. The scientists

typically recognized that, but still chafed a lot at the restrictions

and maybe what looked like lack of respect sometimes to the

scientists, that they couldn't get their views heard by the

engineers, and when they could get listened to, there was

this long, complex system of reviews and reports and discussions

that had to go on before even the smallest thing was changed.

So during the Apollo Program, there got to be quite a conflict

between the scientists and the engineers. At least on the

surface there appeared to be. As we progressed from the Apollo

11 mission to the later Apollo missions and the engineers

got a little bit more comfortable with the missions, the scientists

were able to play a larger part. They were, of course, involved

in the actual mission operations helping to plan what the

astronauts would do and where they could go and what kinds

of samples they would collect and what kind of tools they

would use and that sort of thing. But later on in the Apollo

Program, the engineers even offered some opportunities for

doing some new experiments.

By the end of the program, there was quite a lot of respect

among the scientific community for the way in which the engineers

pulled this all off. I remember a real highlight of those

days was a party, actually, that was held after Apollo 17,

which was explicitly set up to invite a bunch of the key engineers

on Apollo and a lot of the key scientists together. It was

quite an emotional kind of event where the scientists essentially

got up and thanked the engineers for doing what they did.

I think it was a memorable event.

Read

Michael Duke's oral history transcript: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/DukeMB/dukemb.pdf

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Farouk

El-Baz, interviewed 11/2/09

What do you mean, orange

soil?

Apollo 17, when Jack Schmitt mentioned orange soil at the

site, “What do you mean, orange soil?” He talked

about this might be fumarolic activity. Fumarolic activity

is mostly at the very end of volcanic eruptions, meaning that

it is rather recent, last million years or something. We had

no idea that the Moon could have been surviving alive that

long. Everything has died on the Moon three billion years

ago we thought. Actually there is oxidation of the material,

because this red-orange color can come with oxidation of iron.

Does this mean that there is water vapor that is hot that

oxidizes things on the Moon? This is another Moon altogether.

What is this?

This is when I communicated to Ron Evans through the CapCom

to see whether he can see that thing, orange soil. It is at

Shorty Crater; he knows where Shorty is. “Look at Shorty

Crater, look at the northwest corner of Shorty Crater. See

whether you see some orange color.”

He said, “Yes, I can see, I can actually. There is some

orange coloration on the rim.”

“That’s great. Now look any other place, especially

at the other edge of Serenitatis. Do you see any other, any

similar color to that?”

He comes in. “Yes, I see a whole lot of them.”

So we thought that it’s not a unique thing, it’s

not part of this, and it doesn’t have to be fumarolic

activity or oxidation. It is something that maybe impacted,

so these were three or four individual observations that had

an impact on our thinking about the Moon.

Read

Farouk El-Baz's oral history transcript: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/El-BazF/el-bazf.htm

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Jan

M. Evans, interviewed 8/7/03

Everybody

felt a part of this program

A personal [memory], which was very emotional

for all of us, Jamie and Jon and Ron and myself, was after

the fellows returned from Apollo 17. Of course, we were out

at Ellington to meet them. I don’t know if you’re

familiar with El Lago, but Lake Shore Drive is an entrance

that comes in there and curves around by the lake and then

curves up, and another block up, and then you would turn into

our cul-de-sac.

Both

sides of the street, all the way from the entrance into our

cul-de-sac, was lined with flagpoles with the flag flying.

That was just a bit overwhelming. That was something that

the whole community decided to do, and all the children in

the community had been informed about it, or so I found out,

and there were people on horseback carrying flags, and any

child that had a bicycle or tricycle had red, white, and blue

decorated streamers and in their wheels and everything.

Everybody

felt a part of this program and a part of this community.

They were proud.

Read

Jan Evans' oral history transcript: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/EvansJM/evansjm.htm

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Eugene

F. Kranz, interviewed 1/8/99

This

is the ultimate pass/fail

The Mission Control logo is an interesting

one. At the conclusion of the Apollo 17 mission, we had established

a set of values. You know, I talk to people all over the world

now. I talk about leadership, the kinds of people we had,

I talk about trust that developed between the team, I talk

about the values of this team: commitment, teamwork, discipline,

morale, tough, competent, risk, sacrifice. I can quote these

terms out to these people.

It was these values that built the chemistry, because these

are young people. They've never been tested, they've never

been tried before, but it's the chemistry that builds within

the team so you know within a second whether a person needs

help or not. It's a chemistry that builds intuitive communications.

It's chemistry that locks people together when things get

tough. It's the trust between controllers, flight directors,

and crew and even program management that allows us, when

things get tight, to make the seconds count, to pick directions

and move off in this direction with only a fraction of a second's

thought about it and nobody pulling off in a different direction.

So it's this amazing place called Mission Control, which is

an incredible leadership laboratory. People talk about pass/fail.

Well, this is the ultimate pass/fail.

As we were approaching the end of the Apollo Program, I was

looking for some way to leave a legacy for everything that

we had ever learned in Mission Control for the next generation

of controllers, as [Chris] Kraft had left the legacy of the

flight director. A flight director's got probably the most

interesting job description in history. It's only one sentence

long: "A flight director may take any action necessary

for crew safety and mission success." That's it. I think

in American life today in the military there is no job description

that is that simple and so frank and so straightforward, no

ambiguity. So, Kraft had basically left that legacy.

I wanted to leave now the legacy of Mission Control, and I

was trying to find a way that everything that Kraft and myself

and [Glynn] Lunney and [Cliff] Charlesworth and [Gerry] Griffin

and [Peter] Frank and [Milt] Windler—I mean, everything

we had learned, everything that we packaged in these first

13 years of space.

Read

Gene Kranz's oral history transcripts: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/KranzEF/kranzef.pdf

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

William

R. Muehlberger, interviewed 11/9/99

We

did a sneaky thing

We did a sneaky thing on Apollo 17, because

there we had the only scientist that was ever flown to the

Moon, as well as Gene Cernan, remarkable, capable pilot. Their

first field trip was with Bob Parker along with them. Bob

was their CapCom. He's a physicist Ph.D. I had one of the

NASA geologists [Gary Lofgren].

We all flew to El Paso, rented a station wagon, and I took

them all through the Big Bend country. We'd stop at some place

and I'd turn my back to the things we were looking at, and

said, "Describe it to me." And Cernan turned out

to be remarkably good, he had a nice capability of describing

things and what's there. So we figured, well, Gene could pick

up this aspect. How are you going to have two people whose

trainings are so different working as a team? You've got to

each do that. Well, they ended up, I think, a remarkably good

team.

In the science back room we had a TV camera that looked at

the geologic map that was projected into Mission Control.

So when you're looking at Mission Control, it was the left

most screen, which was never up on public TV because Captain

Video's cameras were looking across at the opposite side,

which is the action that was going on on the Moon and down

to the CapCom and that kind of play.

So, on that thing we would put a note, "Here's the time

of arrival at this spot, the time of departure, and the tasks

to be done there." So at each place then that was slipped

on so it would be up on the screen, so the CapCom could see

it. As things were done, we would check them off, so we could

make sure that the crew was carrying it through at the timing

that was available.

So when [Jack] Schmitt was running around, we'd make up a

new one and then remove the first one, and that became what

we did at that spot. In effect, he was running the mission

from the Moon. I was the official one. But what the heck?

I can't see that stuff like he can. Besides that, he knows

it better in the first place.

While Schmitt was doing that, that was about a minute he had

available to do that, Cernan got out, got the tools off, set

the TV antenna so we could start getting TV, started the gravity

meter so it could detect the pull of gravity, and then we

started the tasks. On the time line, Schmitt had a whole bunch

of stuff listed in there, all just plain baloney, tasks that

he was doing. So the time line was full. We were covered.

But we set it up this way. All of those within the geological

world certainly knew it, and I had a sneaking hunch that the

top brass knew it, too, but this is a practical way out, and

they didn't object. That, I guess, is the key point, to have

it done that way….

Send

scientists

The other thing Jack did at the end of each

place as they're driving off, he summarized everything that

he'd seen and learned, so by the time they landed in the Pacific

Ocean, we'd written a report about that landing site that

was better than the one we used to write for the previous

missions, the ninety-day report, ninety days afterwards where

the rocks were all opened, you had a chance to see them, you

had all the film, you had the chance to talk to the crew,

and integrate that to the "Here's what we did on the

Moon." We had one that good before they landed, and then

it grew from there. My judgment, of course, is send scientists.

It happened.

Read

Bill Muehlberger's oral history transcript: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/MuehlbergerWR/muehlbergerwr.pdf

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Richard

W. Nygren, interviewed 1/12/06

The

Moon was dull

It turned out that we were

driving down there the night of Apollo 17, and Apollo 17 was

a night launch, so we were about halfway between Cocoa Beach

and Miami where we pulled off on the side of the beach to

watch the launch.

That was just absolutely spectacular, just unbelievable, being

as far away as we were, and the Moon was dull compared to

how bright that Saturn V was in the sky. It just lit the sky

up, just unbelievable.

From that angle, arching out over the ocean, you could actually

see the arc part of it, where when you’re sitting at

KSC in that area and it takes out, it almost looks like it’s

in a straight line, so you don’t see the arc to it.

It just looks like it’s going straight up. But it was

a beautiful flight to go down there.

Read

Rick Nygren's oral history transcripts: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/NygrenRW/nygrenrw.htm

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Robert

A. R. Parker, interviewed 10/23/02

Not

everybody gets to do that.

Mission scientist was really the interface

between the crew and the science community. Now, that’s

different and funny when you’ve got Jack Schmitt, who’s

a geologist and is going to interact with any scientist he

wants to. It’s not like had it been Joe Engle. If it

had been Joe, I’d have been the interface between Joe

Engle and Gene [Cernan] and the scientists, no questions about

it. But now I’ve got Jack in there, and, well that was

just one of those things which made it easy and hard, I guess.

Jack and I worked very well together.

As mission scientist, I went to most of the science team meetings.

You knew what was being planned, what the rationales were

behind that. At the same time, Jack had training. He had lunar

module training. He was the lunar module pilot. So he had

training for the command module, lunar module, and all those

things. So he couldn’t go to all those science team

meetings. So essentially I’m there as his representative,

even though he’s the scientist as well….

And of course some of it was great fun. I mean, Jack and I

spent nights down at the crew quarters naming the craters,

because every crew got to name the craters; it was the good

way of talking about where they were. And Jack and I spent

time naming a lot of the craters in the landing site. Hey,

not everybody gets to do that.

Read

Bob Parker's oral history transcript: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/ParkerRAR/parkerrar.pdf

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Granville

E. Paules, interviewed 11/7/06

All

right, I’m retired

Apollo 17 was the last mission, and it was

a night launch. I’d never seen any launch, Apollo launch.

I’d been out to see the vehicles being crawled out to

the launch pad and went up in the VAB in the very top, and

got to look in the spacecraft after it’s been all assembled

and everything, but I’d never actually seen a launch.

So I said, “All right, I’m retired.” So

we all went, and I took the family. We were going to go down

and watch the launch. Well, we had it all set up, and remember,

it slipped a couple of days, and our flight and everything

was all set up; we had to go back. But on the last day with

the last minute of the last hour or something, they finally

got the thing off, and I have all these movies of it. I took

still 35mm shots while my wife was taking movies of it.

You

could feel it in your bones

It was really exciting, because it’s kind of a great

way to end your career and that particular notch in your career,

because you got to see the thing really happen. There’s

nothing like being at a launch, even though you’re not

really close to it. The launch vehicle looked about this high

[gestures] out at arm’s length, probably.

But when you see it lighted and the engine light at night—you’re

not expecting the shock wave actually to get all the way over

to where the viewing areas were, but all of a sudden you can

see all these birds take off. Flocks of birds take off, these

seabirds between you and the launch vehicle, as this shock

wave comes rolling toward you. You can see that the brush

and the trees all wiggle. You’re still not expecting

this thing, and it all of a sudden it hits. It’s really

very, very exciting. It just rumbles, and it’s a really

deep rumble.

I went to a Shuttle launch later when I went back to work

for Space Station, and the Shuttle, I compare them in the

Navy to like a 16-inch gun firing—which is a real deep,

and the whole ship shakes and everything—to a 5-inch

gun. This is the size of the bullet, 16 inches across versus

5 inches across. The 5-inch sounds like a really sharp crack.

It’s just a crack, really different, and the Shuttle

sounds the same way. It crackles when it takes off.

The Saturn V would just kind of—you could feel it in

your bones. It [rumbles] all the way through, even where we

were standing.

Read

Gran Paules' oral history transcripts: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/PaulesGE/paulesge.pdf

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Philip

C. Shaffer, 1/25/2000

You

can't get there from here

At that point, Bill Tindall got his revenge,

and I became the chairman of the data priority, and off we

went with all the rest of the lunar missions, planning those,

the J missions, the ones that a rover and the full-blown scientific

instrument complement in the service module. That was very,

very much more complex in getting all of that done.

I got involved a lot in landing site selection at that point,

too, but it was as the data priority guy, mission techniques

guy, rather than any other role. I remember the selection

for Apollo 17, the geologists wanted to go to Taurus-Littrow,

the crew was interested in going to Taurus-Littrow, and the

trajectory guys say, "You can't get there. It's too narrow."

Taurus-Littrow has got a 200-foot scarp cliff at the end of

it and it's got these 6,000-foot mountains on each side, but

this scarp is 200 feet of lunar crust, it's exposed. One of

the mountains has had a huge slide and you can see the debris

material that's down on the floor. There's impact craters

there. There's volcanoes there. I mean, everybody wants to

go, but the trajectory guys are saying, "You can't get

there from here."

The argument escalated, and finally we ended up in the presence

of Chris Kraft about landing site selection for Apollo 17.

Chris listens to the scientists make their plea and the trajectory

guys doing their doom-saying, and then he looked at me and

he said, "Well, what do you think?"

I said, "Chris, you ought to go. Let's go. We can do

that."

So Bill Muehlberger, who was the geologist guy, he made up

a plaque for me for that one, with a little rhyme, basically

acknowledging the role that I'd gotten to play in picking

that landing site.

Read

Phil Shaffer's oral history transcript: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/ShafferPC/shafferpc.pdf

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Leon

T. Silver, interviewed 5/5/02

Who

said that first?

The first time I had to work alone with Gene

[Cernan] and Jack [Schmitt] was in the San Gabriel Mountains

behind Pasadena. After I got through with that exercise, I

had the following impression. Gene was his own man. He was

going to learn from Jack Schmitt, an experienced geologist,

as much as he could. But he was a man of his own observations

and his own opinions, and they were very good. When I got

through, I had them do some similar things that gave me a

basis for comparable comparisons, and Gene, at this stage,

was quite good. I’m not going to compare him to Jack.

Jack knew so much more than he did. But at a comparable stage

to 13 or 15 or 16, even, he was good.

And from then on, through the whole training experience—and

I did not run most of the exercises that they were on, but

I ran several—I found that I could get value from Gene’s

comments, and I wasn’t expecting Jack to be the voice

of the team, and Gene Cernan as commander would never allow

him to be the voice of the team, and I found him to be very,

very good. So Gene did a first-rate job, from my point of

view as a science trainer….

I ran into a very interesting difficulty. Their voices have

very similar timbres, and telling them apart was, “Who

said that first?” And they saw interesting things. There

was a station on their second EVA called Station 4, Shorty

Crater, the crater with the dark rim around it. We thought

it might be something that we had anticipated on the Moon,

but we had never found: a volcanic crater, as opposed to an

impact crater. But it wasn’t. It was a crater which

had a very distinctive deposit that had been thrown out of

the crater.

Boy,

was I excited

And these guys drove up to the rim of Shorty’s

Crater—and now I’m going to run into trouble.

Somebody said, “Look down there. It’s orange.”

I don’t know whether that was Gene or Jack. I think

Jack said it, but I’m not sure.

That got us terribly excited. Now, why? Well, you have to

be geological to know this, and that is that in basaltic craters

on Earth where water is present, the presence of steam coming

up through the black rocks contributes to the oxidation of

the iron in the rocks and turns them reddish-orange. Boy,

was I excited. Finally we’d gotten to a place where

we were defining some evidence of oxidation, some water. By

the time we started Apollo 17, we had the impression the Moon

was waterless, it was oxygen-less except for the oxygen incorporated

in the minerals in the rocks, and here was something new.

I got very excited. I was dead wrong. In fact, I was jumping

up and down, and I was calling out to the PI, and it was then

he had to talk to Jim Lovell [CapCom]. I said, “Get

them to take a core. Get them to take a core. Get them to

take a core.” Well, they knew enough to take the core

without my having to say a damn thing, and Bill Muehlberger,

Bill’s a big guy, Bill just pushed me down in my seat,

and he did exactly the right thing, because they did take

care of it. They did it all well.

Hey,

I see orange out here, too

It

turned out to be orange glass and zillions, ten-to-the-fourth

zillions, of little beads. We didn’t know it at the

time. Some of the beads were black. The black halo came from

the black beads, and the crater had dumped into a layer.

Flying overhead was the command module pilot, Ron Evans. Ron

heard these guys excited about orange stuff, and he was flying

over the rim of Mare Serenitatis, and he said, “Hey,

I see orange out here, too.” And he looks, sees orange.

He took pictures which showed that.

Apparently there’d been a major, major event. This was

a volcanic event. These were volcanic deposits of beads, of

melt, coming out into the vacuum of the lunar environment

forming perfect little spheres. That’s one way to make

ball bearings. Subsequently, we learned that the color came

from the presence, instead of an oxidized state, the presence

of titanium 3, a very reduced state of titanium, and it was

one of the most important discoveries we had there.

Read

Lee Silver's oral history transcript: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/SilverLT/silverlt.pdf

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Apollo

17 Information at JSC

The

Apollo 17 Mission

http://spaceflight.nasa.gov/history/apollo/apollo17/index.html

|

| |

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

Return

to JSC History Portal

|

|