Apollo 8 Oral History Interview Excerpts

|

Frank

Borman, interviewed 4/13/99

Apollo

8 mission planning

It’s hard for us to fathom now. But the thing that’s

interesting about that mission was that, I don’t know,

maybe half a dozen of us sat in Chris Kraft’s office

one afternoon and we went over the flight plan, to try to

understand what would we do on the flight. And I’ve

always thought, again, it was an example of NASA’s leadership

with Kraft and their management style that we were able to

hammer out, in one afternoon, the basic tenets of the mission.

You know, the tracking people wanted us to stay up there a

month. I didn’t want to stay more than one—it

was a give-and-take, and Kraft called the shots. So we ended

up going around 10 times, and I never really thought about

going around behind [the Moon]. You’d lose radio contact;

but that’s about all.

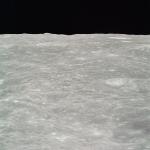

Actually, the far side was lit, because the Sun was over there.

I remember that in order to go 10 revolutions around the Moon,

we had to launch at a certain time; but the recovery would

then be before sunrise. And the recovery people were concerned

about that. But all this was thoroughly discussed, and then

Kraft made the decision. It wasn’t a committee; it wasn’t

a—you know, it was one man who had the knowledge to

fly like that.

The

Christmas Eve message

Well, it’s another example of the wonderful country

we live in. Because Julian Sheer, who was the head of public

information for NASA in Washington, called me one day. He

said, “You’re going to have the largest audience

that’s ever listened to or seen a television picture

of a human on Christmas Eve and you’ve got 5 or 6 minutes.”

And I

said, “Well, that’s great, Julian. What are we

doing?”

He said,

“Do whatever’s appropriate.” That’s

the only instructions. But—and that’s the exact

word, “Do whatever’s appropriate.” Whatever

you feel is appropriate.

And to be honest with you, we were so involved in the mission,

I just kind of farmed that out to a friend of mine, Si [Simon]

Bourgin, and he consulted with some of his friends and came

back with the idea of reading from Genesis. And I discussed

it with Bill [Anders] and Jim [Lovell], and we had it typed

on the flight plan; and I didn’t give it anymore thought

than that.

Looking

back at Earth

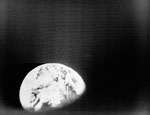

Looking back at the Earth on Christmas Eve had a great effect,

I think, on all three of us. I can only speak for myself,

but it had for me. Because of the wonderment of it and the

fact that the Earth looked so lonely in the universe. It’s

the only thing with color. All of our emotions were focused

back there with our families as well. So that was the most

emotional part of the flight for me.

Read

Frank Borman's oral history transcript: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/BormanF/bormanff.pdf

Christmas

Eve Message, December 24,1968

Apollo

8: Earth's Rise to a New Era

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

James

A. Lovell, Jr., interviewed 5/25/99

On

leaving Earth behind

My first sensation, of course, was “It’s not too

far from the Earth.” Because when we turned around,

we could actually see the Earth start to shrink. Now the highest

anybody had ever been up about 800 mi. or something like that

and back down again. And all of a sudden, you know, we’re

just going down. I reminds me of driving in a car looking

out the back window, going inside a tunnel, and seeing the

tunnel entrance shrink as you go farther into the tunnel.

And it was quite a sensation to think about. You had to pinch

yourself. “Hey, we’re really going to the Moon!”

I mean, “You know, this is it!” I was the navigator

and it turned out that the navigation equipment was perfect.

You couldn’t ask for a better piece of navigation equipment.

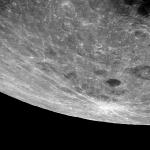

Earth

rise

And by the way, I’ll put everything to rest right now.

As I was coming around, when we saw the Earth coming up, who

took that famous Earth rise picture they made into a stamp

in 1969. Now you’ll likely get a different view from

[Framk] Borman or from [Bill] Anders. But I’ll have

to tell you right now. Now you think I’m going to say

that I took it? For 25 years I said that only to keep the

things going, to keep us young and happy. Keep a little controversy

in the game. Actually, I think Anders took the picture. But

you have to remember, I was the director. I told him where

to take it. I told him how to compose the picture. He just

happened to have a telephoto lens.

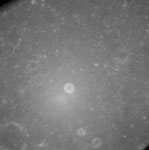

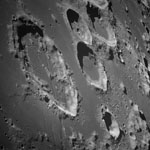

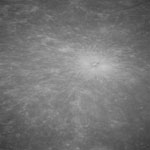

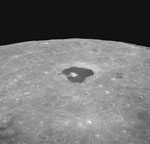

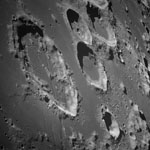

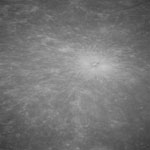

We were

so curious, so excited about being at the Moon that we were

like three schoolkids looking into a candy store window, watching

those ancient old craters go by—and we were only 60

miles above the surface. We didn’t have any kind of

feeling, at least myself, of fear or if, you know, are we

going to get back or not? It was just to be there was such

an exciting moment that we’d have done it all the time.

I felt very, very honored and lucky to be there.

The

effect of Apollo 8 on the world

At the

time, we didn’t know what the effect of the flight would

be. We didn’t know whether the flight was going to be

successful or not. But with riots and assassinations and the

war going on [that year], I was part of a thing that finally

gave an uplift to the American people about doing something

positive. That’s why I say Apollo 8 was really the high

point of my space career.

On Apollo

11, I was honored to be with [Charles A.] Lindbergh watching

the launch from the Cape, and I said to General Lindbergh,

“Isn’t this really apropos? I mean, this is the

most auspicious moment. These people are going to go up there

and they’re going to land on the Moon!” And Lindbergh

looked at me and said, “Well, yes, to a certain degree.”

He said, “But Apollo 8 was the real charger of this

whole program.”

The

Christmas Eve message

When we determined, first of all, that we would get and burn

into the lunar orbit on Christmas Eve we thought, “Boy,

something’s got to be appropriate to say. We ought to

say something. What can we say?” And we couldn’t

think of anything. Then there was a fellow that I think Borman

knew, his name was Si [Simon] Bourgin. Frank asked him, could

he come up with something appropriate? Well, he couldn’t.

But he knew another person, I think he was a newspaper man,

Joe Laitin, and he said, “Okay, I’ll think it

over. I’ll try to see what I can do.”

He was

working almost all night trying to think of appropriate words

and his wife came down and said, “Why don’t you

have them read something from the Bible?”

And he

said, “Well, that’s the New Testament.”

“No,”

she said, “the Old Testament. Read it from the Old Testament

because this would be very appropriate. And most of the people

in the world will be listening in. And most of the people

in the world are not Christian.”

So, that’s

how it came to pass that he said the first 10 verses of Genesis,

which is really the foundation of many of the world’s

religions. So, that’s how it got started.

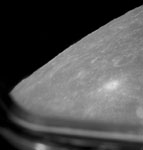

And [as

we read it] at the same time we had this sort of now rudimentary

TV camera, black-and white camera, that was pointing out the

window watching the craters go by and slowly slipping into

daylight.

Read

Jim Lovell's oral history transcript:

http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/LovellJA/lovellja.pdf

Christmas

Eve Message, December 24,1968

Apollo

8: Earth's Rise to a New Era

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

William

A. Anders, interviewed 10/8/97

Saturn

V launch

We had simulated essentially everything we could think of,

or anything anybody could think of on that flight, all previous

flights, and in centrifuges, in zero G airplanes, and procedure

trainers. And yet the very first seconds of the flight were

a total surprise to everybody because the Saturn V, which

is a big tall rocket, kind of skinny, more like a whip antenna

on your automobile, and we were like a bug on the end of a

whip. It actually gets very massive near the bottom, with

the center of gravity near the bottom, so if you rotate it,

what little bit of wiggle on the bottom translates to a big

wiggle up at the top.

These giant F-1 engines, each producing a million and a half

pounds of thrust, were trying to keep the rocket going straight.

So, it was being thrashed at the bottom and we were getting

really thrashed at the top. I mean, violent sideways movement

and massive noise that nowhere near had been simulated properly

in our simulations. For about the first ten, seemed like forty,

but probably the first ten seconds we could not communicate

with each other. Had there been a need to abort detected on

my instruments I could not have relayed that to [Frank] Borman.

So we were all out of it, on our effectively unmanned vehicle

for the first ten or twenty seconds.

The next most impressive thing was that as we burned out on

the first stage. We were hitting about six or eight G’s

and we were back in our seats. You could hardly lift your

arms, you have trouble breathing, but you’re not blacked

out because of the way your blood was flowing from your legs

down into your torso. But, try to reach up, it’s like

you had a twenty pound weight in your hand. All the fluid

in your ears is being pushed back into the seat along with

your body.

Then the engines cut off, and just as they cut off some retro

rockets fire to try to move that big first stage away from

the second and third stage but slightly before it separates.

So, you go from a plus six G to a minus one-tenth, and the

fluid in your ears just goes wild.

I felt like I was being catapulted right through that instrument

panel. Instinctively, I put my hand up in front of my face,

and just about the time I got my hand up, the second stage

cut in. Whack-o, right onto the face plate with the wrist

ring, which left a gash. I thought, “Oh, damn, here

I am, the rookie of the flight, and sure enough here’s

this big rookie mark.” When we got into orbit and I

got out of my seat and we took off our suits and each guy

handed me their helmet to stow, sure enough, each one of them

had a gash in it from the same thing.

This very delicate, colorful

orb

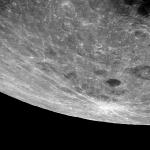

But, the most impressive aspect of the flight was when we

were in lunar orbit. We’d been going backwards and upside

down, didn’t really see the Earth or the Sun, and we

rolled around and came around and saw the first Earth rise.

That certainly was, by far, the most impressive thing. To

see this very delicate, colorful orb which to me looked like

a Christmas tree ornament coming up over this very stark,

ugly lunar landscape really contrasted…. So here was

this orb looking like a Christmas tree ornament, very fragile,

not an infinite expanse of granite and seemingly of a physical

insignificance, and yet it was our home.

Read

Bill Anders' oral history transcript: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/AndersWA/anderswa.pdf

Christmas

Eve Message, December 24,1968

Apollo

8: Earth's Rise to a New Era

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Christopher

C. Kraft, Jr., interviewed 5/23/08

Operational

capabilities

The Marshall Spaceflight Center under Wernher von Braun was

building the Saturn V. They're rocket people. They know the

rocket business. When we flew the first Saturn V, it looked

like it was a great flight, but it wasn't. We had problems

on all three stages, problems on the first stage, second,

and third stage. They were not serious problems on that flight

because it made it. It did its job.

Well, the second flight was a disaster. I want to emphasize

that. It was a disaster. The first stage had pogo (bounce).

The second stage had pogo so badly that it shook a 12-inch

I-beam; it deflected a foot as it was flying in the second

stage. The third stage ignited and then shut down, and it

would not restart, which was a requirement to go to the Moon.

It also had some vibratory problems. Here's the Saturn rocket

that everybody thinks is a wonderful piece of hardware but

it almost busted itself into pieces in all three stages.

In July of 1968, the Command/Service Module had become a good-looking

piece of hardware. That part of the program was really progressing

well, and we all had a great deal of confidence that it would

fly and fly well. But the Lunar Module was a mess. It was

a mess because it had to be light and we were using these

very delicate pieces of structure. Just everything was going

wrong with it and it wasn’t going to be ready for a

while.

During those early Apollo planning meetings, we had set out

various categories with objectives that we wanted to accomplish.

We wanted to prove to ourselves that the hardware was satisfactory

and would accomplish the operational capabilities that we

had set out in terms of rendezvous, docking, heat reentry

capabilities, control, navigation and guidance, et cetera,

et cetera—all needed capabilities to reach the Moon.

We believed it probably would take more than one flight to

accomplish the tasks we required; we thought to prove this,

it'd take us two or three flights.

Turned out it took us one flight to do them all. That was

a surprise to all of us....

Most significant mission ever

Although a lot has been accomplished, Apollo 8 probably remains

as the most significant mission ever flown. The first flight

of the Shuttle from a technical point of view was equivalent.

But not from the total aspect, not from an emotional or the

significant effect on the country and on the world that Apollo

8 had.

Man had been looking at the Moon ever since they could see

and wondering about it, thinking about it, looking at it from

a religious point of view, from an astrological point of view,

from a farmer's point of view, then later from a scientific

point of view. Putting ourselves in the position of having

a man leave the Earth for the first time, being able to look

back at the Earth for the first time, realizing the environmental

aspects of that, —you can just go on and on.

The firsts involved in Apollo 8 almost were unlimited, if

you stop to think about it, from an educational point of view,

a theological point of view, an esthetic point of view, an

art point of view, from culture, scientifically, philosophically,

engineering wise, management wise, scope of capability wise.

Outside of a war, we have never done anything like that in

this country.

That event was a milestone in history, which in my mind unless

we land someplace else where there are human beings, I don't

think you can match it.

It was an opportunity for those of us that were allowed to

do it that doesn't present itself very often in any human

being's life. We were extremely fortunate that all the conjunction

of the stars and the politics and the money and the technology

all came together in the 60s, in '68. That was a very extremely

unique period in man's history from all those points of view.

In the 60s, even though people might not like you, even though

they seemed to be hard to get along with, even though you

thought they were going off in the wrong direction, you knew

you all had the same thought in mind, you knew everybody was

trying to get to land men on the Moon. We were given an opportunity

to do it, and we did it. But that's a characteristic of the

American human being. That's what makes us great.

Read

Chris Kraft's oral history transcripts: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/KraftCC/kraftcc.pdf

Christmas

Eve Message, December 24,1968

Apollo

8: Earth's Rise to a New Era

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Glynn

S. Lunney, 1/28/99

A

very courageous and bold decision

We went to the Moon on the second Apollo manned

flight, Apollo 8. We'd never have had the courage to do that

if we didn't have the experience that we had in the Gemini

Program, both the flight crews, the ground crews, planning

teams, the engineering teams.

We were ready, and as soon as we got the launch vehicle and

the spacecraft that could go there, it was a very courageous

and bold decision that became Apollo 8, but the teams of people

were ready for it. They were ready for it, and it was a result

of what we learned and what we matured through the Gemini

experience. I mean, it was a real training ground for us….

Let's

go for the mission that it was designed for

The [Saturn V] engine testing had gone well,

[and] once we were getting to the point of saying we were

going to put people on board, you know, you're going to light

this thing and fire it, so we got to the point of saying,

well, as long as we're going to do that, we're taking all

of the risks, we might as well try to get the best gain that

we possibly can out of it. You could have used the Saturn

V to do an Earth orbital flight, but it was oversized for

that, and you wouldn't have gotten a full, complete test of

it, or people might have fired the engine in such a way in

lower Earth orbit to keep it in lower Earth orbit but still

fire the engine the whole duration. And we began to adopt

the attitude, well, as long as we're going to fire this thing

the whole way, then let's go for the mission that it was designed

for and take it out to the Moon, which was done on Apollo

8.

So once we got over the initial problems that we had on 502

[Apollo 6], the unmanned flight, and saw that those things

were fixed, then it became a matter of getting used to the

idea that, well, we're going to light this thing, it's going

to burn full duration somehow or another, in some direction

or another, so instead of going sideways, why don't we go

to where we want to go; go to the Moon.

Once you decided to take the risk of putting people on it

and firing it for full duration, you might as well fire it

at the mission that it was designed for, rather than some

strange thing that would have been less than a lunar mission

but still would have entailed all the risk of firing the engine

and running it full duration, firing the stages and firing

them for the full duration that they were planned for. So

once we got used to that idea, we said, yes, let's get on

with it….

Apollo 8 was great. Apollo 8 was kind of like the door opener

for the lunar landing mission. I think all the people, certainly

in the operations team—the flight crews, I think, didn't

feel quite the same way—but for us, all that had to

be done to plan and execute the Apollo 8 mission says that

we really knew how to do that. We opened the door so that

the next couple of flights were test flights. Getting to the

lunar landing mission was shorter than it otherwise would

have been, but we got there with confidence as a result of

Apollo 8.

Read

Glynn Lunney's oral history transcripts: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/LunneyGS/lunneygs.htm

Christmas

Eve Message, December 24,1968

Apollo

8: Earth's Rise to a New Era

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

John

W. Aaron, interviewed 1/18/00

The

importance of Apollo 8

We had no idea when we were flying Apollo 7—at least

I didn't and most of the team here—that there was also

a plan to take Apollo 8 to the Moon if we were successful.

We were totally in the dark about that, because there was

a small group off planning that. When they announced Apollo

8, I just couldn't believe it, but we were all over George

[M. Low] to go try it, because we were young enough to try

anything.

To me, Apollo 8, if you just had to plot a graph of the pinnacle

of the exciting part of my career, that was probably the peak,

more so than the landing on Apollo 11. Now, that probably

sounds funny to say that. Well, two reasons, I think. One,

just the boldness of it, that it was announced over such a

short interval. In my case, being a command and service module

systems person, systems flight controller, it was the vehicle

that I watched when I had the prime stage, and the fact that

it was first and it was going to be done over Christmas, I

mean, looking back on it, that was the pinnacle.

The lunar landing, the actual landing on Apollo 11 ranks right

up there, and I don't think I'm unique there. You ask people

like me. I think they'd probably say Apollo 8 was [the pinnacle].

I was very surprised on Apollo 8, because I had helped make

some calls to correct a couple of anomalies with both the

command module on the way out to the Moon, and so I was very

surprised when they came around the Moon and started naming

off craters and they named one after me. It bowled me over.

I would have never had thought they were going to do that.

So that was a big surprise.

The Christmas Eve message

And then the other big surprise, of course, because we were

all sitting there with our fingers crossed, because we were

in lunar orbit and we couldn't wait to get out of lunar orbit,

I remember that, but when the crew came around the horn from

the far side of the Moon and started reading from Genesis.

To watch the reaction in the Mission Control Center, because

here we are, totally concentrating on our technical job, and

for that to happen, it just didn't occur to us, because none

of us had any clue that was going to happen. And it took us

a while to realize what was happening, the significance of

that, and—wham!—it hit us. I mean, looking back

on it, nothing could have been more perfect of a thing to

have been said.

I think it not only impacted everyone in Washington, but it

particularly impacted the mission controllers, because they

were sitting there doing this highly technical jargon-oriented

job, and then just the transition from that to a reading from

Genesis, that was the big surprise.

A bold move

Apollo 8, of course, culminated a lot of things, because we

had spent so much time redesigning the spacecraft, it seemed

like a lot of time then. In today's world it doesn't seem

much time at all, because what we do now in years we judged

then in months. We just completely redesigned the vehicle,

had one test flight on Apollo 7, and then made the decision

to go to the Moon, and it was highly successful, not only

the spacecraft, but the Saturn V. We forget sometimes the

shaky start the Saturn V had. We had 501 and 502, and those

were not anomaly-free missions. Had major anomalies with the

boosters on those two unmanned flights. So it was a bold move.

Read

John Aaron's oral history transcripts:

http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/AaronJW/aaronjw.pdf

Christmas

Eve Message, December 24,1968

Apollo

8: Earth's Rise to a New Era

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Richard

H. Battin, interviewed 4/18/00

There

was another exciting thing on Apollo 8. When they disappeared

behind the Moon, they were going to have to make a major velocity

change to get into lunar orbit, and that took place when nobody

could see them.

A lot of nervousness there. Our system had to work. If it

didn't, we might never see the astronauts again. It could

be that they would make a correction which would send them

crashing into the Moon, or the whole thing might blow up when

they turn the engine on, and you'd never know it. So there

was a lot of anxious moments there till they appeared coming

out from the other side.

When they came out, they announced their position and velocity,

and the ground people said, "What are they talking about?

We haven't even had a chance to track them yet. How do they

know what their speed is and where they are?"

They forgot they had an onboard system that was telling them

all that stuff. So it took a while for the ground folks to

realize that there was all this capability they had on board

and it really worked.

Read

Richard Battin's oral history transcript: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/BattinRH/battinrh.pdf

Christmas

Eve Message, December 24,1968

Apollo

8: Earth's Rise to a New Era

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Jerry

C. Bostick, interviewed 2/23/00

Planning

the Apollo 8 mission

Several months before we flew Apollo 7, which was the first

manned mission that actually made it into orbit after the

horrible catastrophe that we had with the [Apollo 1] fire,

a few people had been challenged by Chris Kraft to go figure

out why on the next flight, which turned out to be Apollo

8, that we couldn't go all the way to the Moon, which was,

in retrospect, a very aggressive move. Here we were, we'd

had the disaster, the Apollo 1 fire, and totally redesigned

the command module, and we hadn't even flown it yet to prove

that it would work, and here we were working on going to the

Moon, which at first was a big shock.

In fact, the first meeting when I was called to Kraft's office,

I think it was just me and Gene Kranz and Arnie Aldrich, as

I recall, and he asked us to look into the possibility of

going to the Moon with the second flight. And I thought, "This

man is crazy. What are we talking about?" But by the

time we left the meeting, you know, I was already thinking,

well, okay, why can't we, and what do we have to do, and what

we have to accelerate. Within a couple of days, we figured

out there's really no reason why we can't do this, which I

think is the boldest, most aggressive thing that ever happened

in the manned space program….

We had just totally redesigned the Apollo spacecraft, had

never flown it to see if it was going to work or not. We had

a very logical path laid out to get to the lunar landing,

and it involved at least two more flights in Earth orbit.

So at that point we were a long way from thinking about flying

it to the Moon. The capability that we had in the Control

Center was not ready for that.

My initial reaction is, "Hey, we aren't ready for this.

What are you talking about? We've got a plan here. We've got

to go through 7, 8, 9, 10, and then maybe 10, we go to the

Moon. But not on 8, not the second flight around." But

after a small group of people looked at it for a few days,

we couldn't come up with any reason why we couldn't do it,

and started a lot of detailed planning.

Our bosses didn't even know it. I couldn't tell [Glynn] Lunney,

for example. John Hodge was my division chief at the time.

I couldn't tell him that we were working on this. We were

having to steal computer time over the weekend. We'd go back

to Chris and say, "Well, I need these two other guys

to be involved," and usually he would say yes. Sometimes

he would say, "Okay, well, you can get one of them, but

not the other." They just didn't want the cat out of

the bag until a real thought-out decision had been made.

Translunar injection

I remember probably as much or more about Apollo 8 as any

other mission, just because it left such a lasting impression

on me. We had so many firsts, starting with translunar injection,

and it hits you, “My God, we're leaving Earth.”

I mean, translunar means you're going to the Moon, and oh,

by the way, you're leaving Earth and somewhere up there you're

going to hit a point where you're going to leave the gravitational

influence of the Earth and be under control of the gravitational

influence of the Moon.

We're shooting for a target that's not there yet. Translunar

injection is kind of like duck hunting. You don't shoot at

the duck; you shoot way out in front and let the duck fly

into it. So we're aiming at this point up in the sky, and

we're depending on things we've never done before, tracking

data, computing maneuvers, relaying the information to the

crew, loading it in their computers, and doing all this. A

lot of miracles and magical things, almost, have to fall into

place to make it all successful.

When you consider the margin of error and how, as viewed from

the Earth, that the altitude that we were shooting for above

the Moon wasn't even as thick as a sheet of paper. So there

were a lot of firsts involved, a lot of memorable events.

The fact of when it occurred, over Christmas, also was extremely

special after translunar injection. And we're all fairly intelligent

people, we knew what we were doing, but I tell you, for at

least a half an hour there were a lot of us standing around

looking at each other saying, "We're really going to

the Moon. We've got these guys headed out of Earth orbit.

They're leaving us." ...

We did very detailed minute-by-minute return to Earth planning.

Okay, if this happens now, then we'll have thirty minutes

to figure it out. Okay, so here's a time we can fire up the

engine and then come back to Earth and where we'll land. I

mean, we probably way overdid that, but in a situation like

that, there's no way to overdo it, because you can't be cut

short....

The dark side of the Moon

Then the next big thing was when they go around behind the

Moon and we lose contact. All the flight controllers kind

of sit there and after a while they realize we have no data,

we can't talk to them, this would probably be a good time

to take a break, but we don't take breaks. [Laughter] It was

kind of awkward, it really was. We can't desert them, all

get up and leave the Control Center, but for the next twenty-five,

thirty minutes, however long it was, there's no way we can

talk to them, we have no data, so why not? So there was a

big rush on the restrooms then all of a sudden.

And

tremendous satisfaction, by the way, on the part of the people

in the trench especially. When we did lose them, lost the

signal as they went behind the Moon, it was [snaps fingers]

exactly when we had predicted it. So, yes, orbital mechanics

works. God works. He brought the Moon in exactly the right

spot at the right time.

Then a very similar thing when we had acquisition of signal

on the way back, as they came around from the back side of

the Moon, it had to be one of the happiest moments of my life

and for most of the people, I think, in the Control Center.

Again, it was, hey, orbital mechanics works, and there has

to be a God, because he's doing his part.

Then when the crew started reading from the Bible, I think

it was the first time that a lot of us could relax enough

to say, "Hey, we just sent people around the Moon and

it's Christmas. And they're reading from the Bible and relating

this, 'God created the heavens and the Earth.' This is unbelievable."

Read

Jerry Bostick's oral history transcripts: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/BostickJC/bostickjc.pdf

Christmas

Eve Message, December 24,1968

Apollo

8: Earth's Rise to a New Era

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Eugene

F. Kranz, interviewed 1/8/99

Mission

Control during Apollo 8

We then went into Apollo 8, the first mission to the Moon.

This is one where I was almost glad I was sitting on the sidelines.

Mission Control and the flight directing business is really

amazing. It always seems that the people who are watching

the mission get more emotionally involved in the mission than

the people who are doing it, because the people who are doing

it have got to be steely-eyed missile men, literally. I don't

care whether they're 26 years old or 35. The fact is that

you've got to stay intensely focused on the job. It is the

people who are sitting in the viewing room, I think, who have

it the toughest, flight directors who are trying to find a

way to plug into somebody's console so they can listen in

to what's going on.

I think that was probably the most magical Christmas Eve I've

ever experienced in my life, to actually have participated

in a mission, provided the controllers, worked in the initial

design and the concept of this really gutsy move, and now

to really see that we were the first to the Moon with men.

We were at the point where we were setting records, literally,

in every mission that we flew in those days, because the Russians

had long since ceased to compete; it was obvious that we had

the best opportunity for the lunar goal. And this was just

a magical Christmas. I mean, you can listen to [Frank] Borman,

[James A.] Lovell, [Jr.] and [William A.] Anders reading from

the Book of Genesis today, but it's nothing like it was that

Christmas. It was literally magic. It made you prickly. You

could feel the hairs on your arms rising, and the emotion

was just unbelievable….

Certain of the crews at certain times just seemed to have

a magic ability to select the right thing and do the right

thing at the right time, and Apollo 8 was one of those days.

I was just happy as all get-out that I was one of the few.

Glynn Lunney used a term, that as flight controllers working

in Mission Control, to be flight directors or as a member

of the team we were always drinking wine before its time,

because we were doing things for the first time. We were working

missions that people a century from now are going to read

about, but we never had time to really savor it, because as

soon as we finished one, we'd be on to the next.

As a flight director sitting off-line, not working the mission

this time, I did have an opportunity to really savor, to really

get emotionally involved with what was going on, where the

people working the console never had that chance. I mean,

they've got to stay focused, and if they get out of line for

even a second, that flight director's going to come down and

say, "Okay, everybody get your eye. Get squared away.

Get back to business. Let's cut all this crap out." It's

interesting to live in that environment.

Read

Gene Kranz's oral history transcripts:

http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/KranzEF/kranzef.pdf

Christmas

Eve Message, December 24,1968

Apollo

8: Earth's Rise to a New Era

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Joseph

P. Loftus, Jr., interviewed 10/27/00

You

can't flinch

But I think, in a sense, Apollo 8 was a more daring event

for me. That was one of those decisions that you could never

get a committee to make. George Low, in effect, said, "Why

don't we do that," and he was saying it in such a way

that said, "We're going to do that unless you can prove

to me there's some reason we shouldn't." And he talked

with a number of people, and I was in some of those conversations,

and we made the decision to go do it.

It was a real event to go into orbit around the Moon the first

time. To give you some sense of it, imagine you're going down

the highway at 80 miles an hour and you can see a train begin

to cross the highway, and you keep going 80 miles an hour

and the train keeps crossing the highway.

You wonder, is the train going to be gone when I get there,

or am I going to hit it? Well, going into orbit around the

Moon means that you're going to pass just five feet behind

the train. So you can't flinch.

That was a fairly profound one.

Read

Joe Loftus' oral history transcripts: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/LoftusJP/loftusjp.pdf

Christmas

Eve Message, December 24,1968

Apollo

8: Earth's Rise to a New Era

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Thomas

K. Mattingly II, interviewed 11/6/01

Does

anyone know where the Moon is?

It was the middle of the week sometime, because they called

us all together and said we’re going to have a briefing.

I believe it was Saturday morning. We walked in, and that’s

when they revealed to us that they were going to do the Apollo

8 circumlunar mission.

I remember

from that Saturday morning, it was 24/7 until they got down.

Of all of the events to participate in, you know, I was lucky

because I could do Apollo 11 as well as 8 and then 13.

But being

part of Apollo 8, it made everything else anticlimactic. Our

purpose was to go land on the Moon, but somehow participation,

the angst that went with that Apollo 8 mission was far more

electrifying. I remember after the first set of briefings,

and listening to these meetings, it’s like no one had

ever thought about going to the Moon. We’ve been in

this program for how many years, and yet people are asking

questions that are almost like, “Does anyone know where

the Moon is and how to find it?” And here we’re

supposed to be going.

Tindallgrams

It was built into those beginnings of what they started calling

data priority. There were so many questions, and every one

of them needed an answer. But the difference between designing

hardware and getting ready to fly a mission, this was my first

exposure to how dramatically different that was.

Bill

[Howard W. Tindall, Jr.] came out and started having these

meetings. His initial charter, as I understand it, was just

see if you can figure out an order that we can answer these

questions in, because we can’t do it all at once. Let’s

do the most important ones first. So we started having these

meetings.

That kind of put some sanity and sense to it. It created this

thing we called Tindallgrams. Because Bill Tindall

would listen. These meetings would go on sometimes two days,

and they would be eight in the morning until eight in the

evening, whatever it took. Room filled with people. Not always

a lot of decorum. Bill was after answers. It was nowhere near

as collegial an environment as you see in some organizations

today.

But they were after what was right, and everybody was passionate

about. Everybody was young so they were kind of brash and

there wasn’t a lot of patience anywhere. So some of

those meetings were very, very colorful. Some of the characters

were colorful. At the end of this, you were just inundated

with all of this stuff you’ve heard. And now what?

And the next day you would get this two-, maybe three-page

memorandum from Bill Tindall written in a folksy style, saying,

“You know, we had this meeting yesterday. We were trying

to ask this. If I heard you right, here’s what I think

you said and here’s what I think we should do.”

And he could summarize these complex technical and human issues

and put it down in a readable style that—I mean, people

waited for the next Tindallgram. That was like waiting for

the newspaper in the morning. They looked forward to it.

Read

T. K. Mattingly's oral history transcripts: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/MattinglyTK/mattinglytk.pdf

Christmas

Eve Message, December 24,1968

Apollo

8: Earth's Rise to a New Era

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Dale

D. Myers, interviewed 3/5/99

Our

first critical issue

We had just finished a really terrific flight on Apollo 7.

I think it was George Low who came up the idea of doing Apollo

8, which was to go around the Moon solo with the command and

service module. The problem was, the lunar module was behind

schedule, and if we waited for the lunar module to be ready

to go for the next flight, it looked like there was a good

chance we would miss making it in this decade.

So the idea of coming to the figure-eight around the Moon

came up, and George Mueller sent all of the program managers

in the industry a letter asking them if they were confident

that we could make that flight. Our first critical issue,

the key issue, was that without the lunar module, we were

in a position that if the service module engine failed, the

guys would sail on out into space. So it was pretty important

that we make that thing work.

It had worked fine on the previous flight and we went through

a whole series of detailed reviews on all the elements of

the command module and service module to make sure that everything

was good and everything looked like it was ready to go, all

the equipment had been properly certified and had no anomalies

that looked like it might give us a problem. After a review

with the Aerojet guys and with our people, just totally soul-searching

that thing, I signed off, saying, "I'm confident you

can make that flight." ...

The unk-unks

Now, in retrospect, you look back, we had looked through all

the systems, and we had looked through all the systems of

the service module, which included the oxygen tanks that blew

up on Apollo 13. If that had happened on Apollo 8, we would

have lost those guys, because we had no lunar module to bring

them home.

So even though you have been through all the elements and

you can't find anything that would give you a problem, there

are always what we used to call the unknown unknowns—the

unk-unks. Those are things that are just complete surprises,

and that's what happened Apollo 13, and it could have happened,

something of that nature could have happened on Apollo 8.

Of course, it didn't.

Read

Dale Myers' oral history transcripts: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/MyersDD/meyersdd.pdf

Christmas

Eve Message, December 24,1968

Apollo

8: Earth's Rise to a New Era

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Granville

E. Paules, interviewed 11/7/06

That

eerie feeling

I was the guy on the mission when they went behind the Moon,

so there was a little fine-tuning maneuver we did. The understanding

of the gravity effects of the Moon, we’re still learning

about those, and so you weren’t absolutely, perfectly

clear about how, when you go looping around the Moon, exactly

what the effect on the vector, the spacecraft vector, would

be.

We had done enough simulations. You had enough math models.

They’d had the unmanned spacecraft try to land on the

Moon. So we were pretty clear, but the main thing is doing

it the first time, and these guys on that Christmas Eve go

zipping out there. Everything is perfect. We had no problems

at all with Apollo 8 all the way out. It’s just that

eerie feeling when the guy goes behind the Moon that first

time. That’s the first time that humans had ever been

out of sight of Earth.

There was this quiet period while they’re behind the

Moon the 20-some minutes or so that you don’t talk to

them. The procedure is as soon as they’re supposed to

be in radio contact, the CapCom starts calling them. Well,

they call and call, and it seemed like at least a minute after

they should have been in view before we ever heard from them.

So, the place gets quieter and quieter while you’re

waiting for that first voice contact back from those guys.

Then they went through all the little comments that made all

the history. It was a very exciting time for all of us. That

was pretty unique for a few of us.

Read

Gran Paules' oral history transcripts: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/PaulesGE/paulesge.pdf

Christmas

Eve Message, December 24,1968

Apollo

8: Earth's Rise to a New Era

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

G.

Merritt Preston, interviewed 2/1/00

A

tremendous success

Even Apollo 8, though, you just couldn't believe that they

were going to do that. I didn't have any input into doing

it or not doing it, except wanting to get on with it, but,

boy, I'm telling you that was a huge step. I wonder how the

three astronauts really—they must have gone into that

with a certain amount of destiny in their thinking, because

the odds were greatly unfavorable. I mean, hell, how in the

world could we expect to do that? But we did.

That

was a tremendous success. You know it changed the whole environmental

attitude of the world when they saw that picture of the Earth.

I mean, it did more than to advance the environmentalism than

anything that ever happened.

Read

Merritt Preston's oral history transcript: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/PrestonGM/prestongm.pdf

Christmas

Eve Message, December 24,1968

Apollo

8: Earth's Rise to a New Era

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Rodney

G. Rose, interviewed 11/8/99

It

was a gutsy thing

A lot of people have asked me which was the high point in

the Apollo Program, thinking that it’s Apollo 11. Well,

11 was really something, but I think as the high point, Apollo

8 had to take the vote, because as an engineer, it was the

first time we’d been out there, and we only had the

one engine to come back with.

Now, Rocketdyne and North American and Rockwell would say,

“Well, there was redundancy to the gazoos on that engine.”

I’d say, “Yes, but you only had one nozzle,”

and if anything went wrong with the nozzle, as we found out

on Shuttle not too long ago, a nozzle problem can cause some

gas pain, to put it mildly. So it was a gutsy thing.

Of course, Chris Kraft and George Low and all those people

set the thing up in the late summer, and I got the job of

putting the profile together.

Among other things, at that time, I was on the vestry of St.

Christopher Church in League City, and Frank Borman was a

lay reader there, and so the beginning of October we had the

vestry meeting, and Frank says to the minister—he was

scheduled to be lay reader at Christmas Eve service, you see,

and he said, “I’m going to be on travel,”

because he wasn’t allowed to say where he was going.

Now, I knew where he was going, so I took Frank outside, and

I said, “Frank, I think we can work this. If you read

the prayer and stuff from the Moon, I’ll get it taped

in the MCC and whip the tape over to the church and we can

play it in the service.”

So we went back in and told the minister, “Frank can

do that. He’s decided he can do it.” Of course,

by the time Christmas got near, everybody knew that he and

Jim Lovell and Bill Anders were the crew going, and that’s

when we let the minister in on the secret….

The timing was exquisite

In one of the early—I forget, I think it was about the

fourth or fifth rev around the Moon, Frank comes on and says,

“Is Rod Rose there? I’ve got a message for him

and for the people of St. Christopher. In fact, it’s

for people everywhere.” I’d called the thing “Experiment

P-1,” for first prayer from space. So Frank read that

and we recorded it, and then, of course, they came out with

the reading of the first ten verses of Genesis, which was

super. I had nothing to do with that, other than record it.

So that worked in great, because I got off duty and took [the

recordings] over to the church, and I’d set up with

the guys on duty in the MCC to give me a call as soon as the

vehicle had come around from behind the Moon, because all

our trans-Earth burns from the Moon were made behind the Moon,

so you didn’t know whether it was a good burn or not

until they came back. They’d finished the burn, came

around from behind the Moon, and then that was the big “uncross

your fingers.”

The timing was exquisite, because that happened just before

midnight local time in Texas, and they phoned me at the church

and I was able to give a little message, a piece of paper

to the minister. At that time, we’d had the midnight

communion and he was about to dismiss the congregation with

a blessing, and he was able to tell him that they were on

the way home.

Read

Rod Rose's oral history transcript: http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/RoseRG/roserg.pdf

Christmas

Eve Message, December 24,1968

Apollo

8: Earth's Rise to a New Era

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Christmas

Eve Message, December 24,1968

(Audio/video broadcast)

Apollo

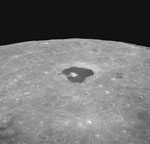

8, the first manned mission to the Moon, entered lunar orbit

on Christmas Eve, December 24, 1968. That evening, the astronauts;

Commander Frank Borman, Command Module Pilot Jim Lovell, and

Lunar Module Pilot William Anders did a live television broadcast

from lunar orbit, in which they showed pictures of the Earth

and Moon seen from Apollo 8. Lovell said, "The vast loneliness

is awe-inspiring and it makes you realize just what you have

back there on Earth." They ended the broadcast with the

crew taking turns reading from the book of Genesis.

William

Anders:

"For

all the people on Earth the crew of Apollo 8 has a message

we would like to send you".

"In

the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.

And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was

upon the face of the deep.

And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And

God said, Let there be light: and there was light.

And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the

light from the darkness."

Jim

Lovell:

"And

God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night.

And the evening and the morning were the first day.

And God said, Let there be a firmament in the midst of the

waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters.

And God made the firmament, and divided the waters which were

under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament:

and it was so.

And God called the firmament Heaven. And the evening and the

morning were the second day."

Frank

Borman:

"And

God said, Let the waters under the heavens be gathered together

unto one place, and let the dry land appear: and it was so.

And God called the dry land Earth; and the gathering together

of the waters called he Seas: and God saw that it was good.

And

from the crew of Apollo 8, we close with good night, good

luck, a Merry Christmas, and God bless all of you - all of

you on the good Earth."

Apollo

8 Christmas Eve Message (40MB, MOV)

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

|

|

Apollo

8: Earth's Rise to a New Era

The audio

documentary, Apollo 8: Earth's Rise to a New Era,

features excerpts of oral histories combined with a narration

to present a unique perspective on a venture that resulted

in humankind's first voyage to another celestial body.

The voices

from these managers, engineers, and astronauts convey the

significance of a mission necessary for the success of the

manned lunar landings that followed. Hearing their emotions

as they speak, soundly reinforces the immediate impact this

mission had on NASA, as well as its effect on a nation's goals.

Narrated

by Clay Morgan, Apollo 8: Earth's Rise to a New Era

was recorded in December 1998 in celebration of the 30th anniversary

of Apollo 8.

Apollo 8: Earth's

Rise to a New Era (5MB, MP3)

http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/apollo8_mp3/Track

01.mp3

|

| |

Return

to December: A Significant Month in Apollo

Return

to JSC History Portal |

|