NASA Headquarters NACA

Oral History Project

Edited Oral History Transcript

Eleanor

"Jerry" Jaehnig

Interviewed by Sandra Johnson

Newport

News, Virginia –

2 April 2014

Johnson: Today is April 2, 2014. This oral history session is being

conducted with Eleanor “Jerry” Jaehnig at her home in

Newport News, Virginia, as part of the NACA Oral History Project sponsored

by the NASA Headquarters History Office. The interviewer is Sandra

Johnson, assisted by Rebecca Wright. I want to thank you again for

agreeing to talk to us today and allowing us in your home. We really

appreciate it. I want to start today by talking to you a little bit

about your background before the NACA, where you went to school, and

when you first heard of the NACA and decided to try to come to work

here.

Jaehnig:

I went to Winthrop University [Rock Hill, South Carolina]. It’s

Winthrop University now. It was just Winthrop College, and it was

a girls’ school. Now, it’s co-ed. I went there because

my older sister went there, and I had a couple of relatives that went

there. In fact, the governor’s wife went there. It was well-known

as a good school. I majored in math. I wanted to major in music, but

my older sister said, “You cannot major in music. You will have

a hard time making a living if you’re in music. Major in math,

and take your music on the side.”

So, I took her advice. I don’t know whether it was a good thing

to do, because my heart was in the music, but it’s a good avocation,

anyway. So, I majored in math. My family could not afford to send

me to school and give me music lessons on the side. My school offered

a contest—a music contest. The only thing you had to do, if

you won, was promise that you would play in the orchestra. I didn’t

play an instrument, but I won the contest. I got the first prize,

so I picked the cello. I got two lessons every week for the four years

that I was in college, so I got my music, but I majored in math. I

love it. I just love math. I’m going crazy about it all the

time. Numbers are my thing. I just do everything that has numbers

in it—the newspaper or anything. If there are numbers, I’ve

got to have it. That’s what I’ve done. I majored in math.

The way I found my job here—they had a scout out in our school.

They were going to all of the universities. They came to my school,

and they interviewed all of the math majors. They interviewed me and

hired me right then. Even before I graduated, I had a job at NACA.

I had quite a few harrowing experiences getting here, though.

Johnson:

What were those? How did you get here?

Jaehnig:

I came on the train. There were four of us that majored in math, and

they hired all four of us. We came on the train.

When we got here, we had a reservation in Hampton [Virginia], in the

Hampton Hotel. We had a friend that was meeting us. When we got to

the hotel, they had already given our room to somebody else, so we

didn’t have a room. They put us in a big, big, old, colonial

home. I think it was something like four stories high. The only room

they had was on the top floor. There were windows on all four sides,

and none of them had screens on them. It was hot as Hades, so we had

to have the windows open.

I was so homesick. The pigeons would fly in one window and fly across

the room and out the other. We were all in the one room, and we took

turns swatting the pigeons out of the windows. I had the worst headache

I’ve had in my whole life, and I wanted to go home so badly.

My mother had bought me all of these pretty, new clothes to wear.

One of the girls’ luggage got lost, I loaned her my clothes,

so she wore my new clothes before I did.

Johnson:

How long were you in that room?

Jaehnig:

About a week. Then, we finally got a newspaper, looked at “for

rent” ads and we got on a bus and went to where the Chesapeake

Boulevard is. It’s on the river between Newport News and Norfolk.

So, this room that was for rent—it was right on the boulevard,

right on the water—a beautiful place. We couldn’t find

it, so we stopped at this big, colonial home there. This elderly man

answered the door. I said he was elderly. He was probably in his sixties.

When he went out on the porch and showed us where to go to where this

house was, he said, “Now, if you don’t like that place,

come back, and I’ll see if I can help you.”

We walked around the block and went back and said, “We didn’t

like that place.”

He said, “Well, come in and we’ll have a talk.”

His daughter had just died. She was in her twenties. She was married

to the ambassador of France, and she died in childbirth. So, they

had a void that they had to fill. We had a big void that we needed

to fill, and so they just took us in, like we were their children.

It was just like moving into a home. It was just wonderful. Everybody

was so good to us. Oh my goodness! He’d put candy bars on the

floor outside our door every night so that we’d have something

to take to work with us. It was just wonderful.

There was a boardinghouse just a few doors down the street, so we

took all of our meals there. We had it made, but we had to ride the

bus to the field—to Langley Field [Langley Research Center].

Unfortunately, I drew the graveyard shift, and so I had to go home

on a bus at twelve o’clock at night by myself. Well, Woo [Cloyce

E.] Matheny—that’s the name of one of the engineers in

the 19-foot tunnel—often rode the bus with me. That’s

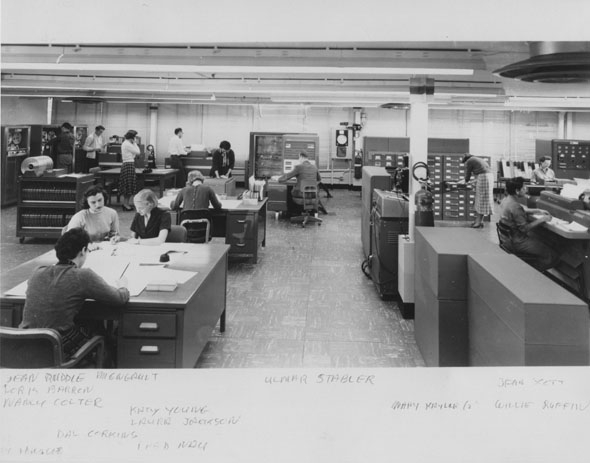

where I was assigned in a 19-foot [Central Computer Pool] as a computer

[Figure 1].

Now, that was back in the days when we didn’t have electric

computers or calculators. I used the slide rule. It was this long,

and this wide, and it had every function on it that you could possibly

have. Well, I had to learn to use that, but that’s where I did

all of my calculations on that slide rule. I had a lot to learn there,

because I was not taught to do that in school. I definitely did not

know how to use it, but my husband did everything on a slide rule.

So, he helped me a lot. That’s what I did, and I was really

very fortunate because I was given a lot of jobs that a lot of girls

didn’t get to have. I really learned a lot of things that, otherwise,

I would not have.

Johnson:

This was in 1943. Is that when you started?

Jaehnig:

Yes, 1943. I worked for two years. I left in ’45 and got married.

In those two years, I learned a lot. In fact, Richard [V.] Rhode—I

don’t know whether you know who he is—he was the section

head. Actually, the whole Aircraft Loads Division was under him. He

finally went to Washington [DC]. Then Phil [Philip] Donely became

my section head. He was very good to me. He gave me a lot of good

jobs and so forth—interesting jobs. Do you know what the V-G

recorders were?

Johnson:

You mentioned that on the phone, so I was going to get you to explain

that and tell me what you did with that.

Jaehnig:

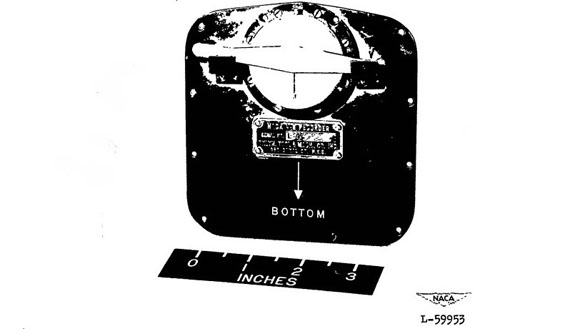

A V-G recorder measures gravity and speed. The two are related quite

a bit. That’s what Phil Donely gave me. I was in charge of that.

What I had to do—they put it on the P-40 [Warhawk “single-seat”

fighter] plane. That’s what the V-G recorder was put on. I would

have to crawl up in the cockpit. Of course, that was in the days before

girls wore slacks. The plane had to be running. You had to smoke a

little glass and put it in, and that would give you a basic curve.

You measured everything from that one curve. The motor had to be running

on the plane when you did that. It would scratch a little line. That

would be the zero [basic] curve, because you weren’t going anywhere.

The pilots were lined up on the side. Oh, gracious! When they turned

that motor on, you can guess what happened. I was pretty embarrassed.

My dress went straight up over my head.

Johnson:

They were lined up, probably knowing what was going to happen.

Jaehnig:

They knew what was going to happen. They knew every bit of what was

going to happen. I got even with them later.

Johnson:

I definitely want to hear that!

Jaehnig:

Then, I would have to go back in the plane, take the glass out, plot

the curve, and work out the equations. That was a very, very good

opportunity for me, which I enjoyed. I just loved doing that. I did

that for almost two years. [Figures 2 and 2(a)]

Johnson:

Were there other women that were up in the planes putting things in

them, or were you the only one?

Jaehnig:

I was the only one.

Johnson:

That was quite an accomplishment for that time.

Jaehnig:

Yes, it was very unusual, but Phil Donely—he was determined

that he was going to make an engineer out of me. He was so disappointed

when I got married. That was okay, too, but he was always very good

to me. I worked the graveyard shift a lot, and that meant I had to

get on the bus at midnight and ride the bus about—oh, gracious—it

seemed like at least 40 miles to where I lived, even though it was

more like 7 miles. Woo Matheny lived about two blocks from where I

lived. That rascal—he got on the bus with me and got off the

bus with me, walked me to my door, told me goodnight, and he walked

home.

Johnson:

That was nice of him.

Jaehnig:

He did that because he did not want me to be walking at midnight by

myself. So, you see—the Lord took care of me. I felt very blessed.

I really did feel blessed. That’s most of my career in [NACA].

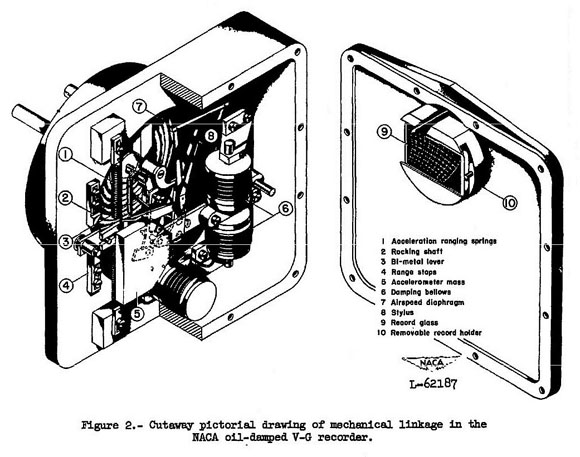

I worked with the V-G recorder. They did also put me in one of the

tanks [Langley Tow Tanks] one time for a short time. We had a couple

of tanks where they did experiments on the water. The tanks were full

of water. You probably never heard of that, but we did have a couple

of those. I did a little bit of stuff, but I don’t really remember

exactly what I did on them. I do remember going into the tank and

taking data at that time. [Figure 3]

Johnson:

That’s interesting. I didn’t realize they did that at

Langley.

Jaehnig:

I can see it right now. It was close to the full-scale tunnel. Another

thing that I had that I thought was so beneficial to me—I got

acquainted with a lot of the test pilots, therefore, that opened up

avenues for me to learn a lot about what they were doing.

I remember Don [Donald E.] Hewes. I don’t know whether you’ve

heard of Don. Don is the one that invented the apparatus that taught

the people that went to the Moon to walk on the Moon [Reduced Gravity

Simulator]. The gravity, of course, is different. Don was an engineer,

he was a private pilot and a very good friend of mine, so therefore,

I got to know him pretty well and what he was doing, too. He was the

one who invented that apparatus.

Johnson:

Was it like a simulator?

Jaehnig:

Yes. It was on the West Area of the field, but there was a big, big

space. The test pilots were the people that used it. They put a harness

around them so that the gravity was different, so therefore, they

simulated the conditions that it would be on the Moon. Don is the

one who invented it—he was lying on the sofa, he said, when

he thought of it.

Johnson:

You never know where that’s going to hit.

Jaehnig:

You never know what’s coming through his head, too. I knew Don

very well. He was a singer, too.

Johnson:

Was he?

Jaehnig:

Yes, we sang a lot together, so I knew him a lot. His wife was one

of my best friends. She just died about a year ago. Don built his

own plane and put a Volkswagen engine in it. They flew that plane

all over the country. It’s amazing. They found him lying under

that plane [at Patrick Henry Airport], dead [he had a heart attack].

That’s how he died—where he wanted to be.

Johnson:

Doing what he wanted to do, I’m sure.

Jaehnig:

You’ve just about got my whole story.

Johnson:

You were fresh out of college and relatively young. What did your

family think when you were going to get on this train and come all

of the way to Hampton by yourself? Well, you had other people, but

young girls travelling and then not really knowing what you were coming

to.

Jaehnig:

Well, you know, my daddy was a pharmacist. He had two drugstores.

It was a tough life, because it was back in the days—it was

during the Depression, and so, therefore, they were happy I had a

job. That’s the honest truth. They were just happy that I had

a job and that I could support myself. In those days, we didn’t

have to worry about our safety. You didn’t. I never felt threatened

or anything—never. Therefore, I felt that I was perfectly safe

everywhere I went. It never occurred to me that I could have been

in any danger.

I had a job that paid well and that was interesting. I was never bored.

I was fortunate that I had people that were over me that gave me credit

for having some sense.

Johnson:

Even today, women have problems with that.

Jaehnig:

Never—in that division, we were always given the greatest respect.

They gave us jobs that really gave us some credit. They really did.

I felt very, very fortunate that way.

Johnson:

Do you remember what your salary was when you first started?

Jaehnig:

I can remember the first one. It was 60 dollars a month.

Johnson:

Oh my goodness! You were excited, weren’t you?

Jaehnig:

That was a lot of money!

Johnson:

When you first came here, coming from South Carolina and then coming

to this area but arriving at Langley, and the wind tunnels and that

sort of thing, what were your first impressions of what you had walked

into?

Jaehnig:

I was probably pretty much awestruck, overwhelmed quite a bit, and

I would go to this huge tunnel—the 16-foot [16-foot High Speed

Tunnel]. The 19-foot was in the East Area. This one was over on the

West Area. Anyway, I went inside of that thing and looked at the propeller.

I was amazed. That thing was big. I had no idea it was that big. Boy,

when they put the air going through that thing, it was a lot of air.

Johnson:

So, you were there from ’43 to ’45? You met your husband

there?

Jaehnig:

Yes.

Johnson:

What was he doing?

Jaehnig:

He was an engineer. He was a civil engineer and some of his work involved

wind tunnel design. He was also a project engineer for the Jefferson

Lab [Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility]. You know what

the Jefferson Lab is. That’s here, but the universities took

it over. He was in charge of that construction when they were building

it. That job just about finished him off. He was really worn out when

that thing was finished, but he travelled all over. There were two

other cyclotrons in this country. One was in California, and one was

in the Midwest. I can’t remember where, though, but he had to

visit them quite a bit.

He was gone a lot. He just practically lived over there at the construction

site. Then, when the universities took it over, he got out of the

picture altogether. He was head of the whole project, which was a

big, big job. He was a smart man. You would never know it, though,

because he never flaunted it. He was a very quiet type of person,

but he knew what was going on all of the time. I think he helped me

a lot with that dadgum slide rule.

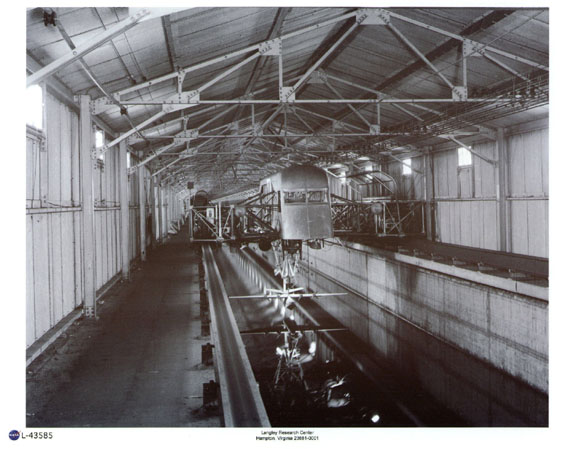

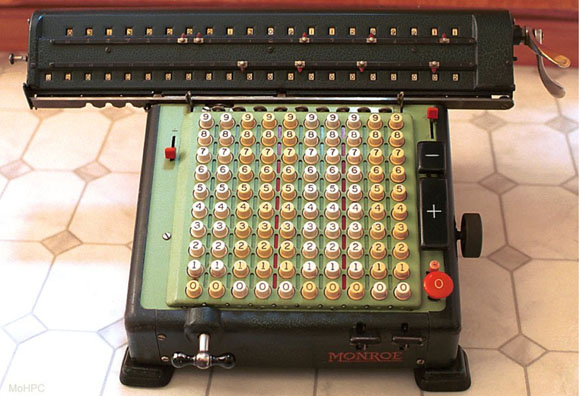

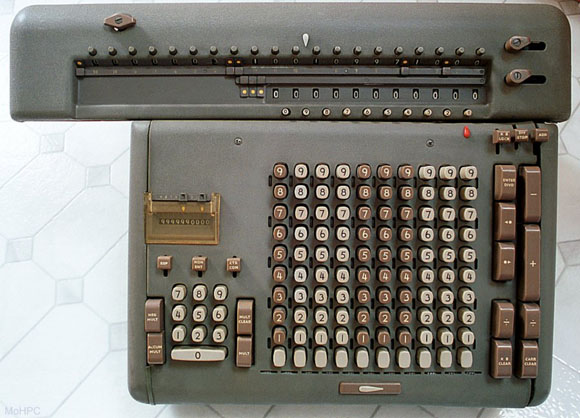

I can remember we [women computers] did not have a calculator. We

finally got a Monroe, which did adding and subtracting. Then, finally,

we got a Friden, and that did multiplication and division and did

the square roots and all that kind of stuff. We were fighting over

those things. [Figure 4]

Johnson:

Were you?

Jaehnig:

Yes.

Johnson:

How many other mathematicians or computers worked in your area where

you worked?

Jaehnig:

The 19-foot was the Central Computer Pool [Figure 1]. That’s

really what it was. I would say—oh, golly—10 or 15 altogether

in the whole office. We were given different jobs to work on. We shared

a desk with somebody else. We didn’t have our own desk. There

were two people to a desk. I can remember the one that had shared

mine. Oh, boy, was he a dilly!

Johnson:

Was he a mathematician also?

Jaehnig:

No. He was not really well-educated. He did equations, but he was

not an engineer.

Johnson:

So, there were some men that were doing the same type of job that

you were doing?

Jaehnig:

Yes. There were very few girls at NACA.

Johnson:

When you started?

Jaehnig:

Yes. Usually, back in those days, everybody went into the computer

pool first, and then you were fed out into different sections after

you had your basic training. I stayed in the 19-foot for a very short

time. Then, Phil Donely took me over. He did a lot for me. He really

gave me a lot of responsible jobs.

Johnson:

Were you the only mathematician, at that time, working for him?

Jaehnig:

I think, probably so, but I don’t remember exactly. There were

not very many girls in there. There were some. We have a couple of

computers living here—Dot Coleman. She lived on my street. Now,

Dot’s health is not good. She went there the same time I did.

We both lived on Kecoughtan Road at one time. Do you know where that

is? That’s in Hampton. They had an apartment—she and another

girl that lived together. They had an apartment on Kecoughtan Road.

I later lived in South Hampton in one of the apartments, but those

were not built when we first moved here. We just had to rent a room

from somebody. Most of it was right around the Chesapeake Boulevard,

in that area. We all had to ride buses to and from work to the Langley

Field. That seemed like a long ride—believe me—a long

one, especially if you’re doing it at midnight. We did take

our turns at the midnight shift. We had several shifts. I pulled my

share of the midnight shift, but I didn’t mind it. I liked the

shift, because it was quiet, and you got your work done. That was

fine. I didn’t mind that at all.

Johnson:

You said you got even with those pilots. I was just wondering if you

would tell us how you got even with them—the ones that were

watching you.

Jaehnig:

That was a pilot that I got even with. He rode a motorcycle. He asked

me to ride the motorcycle with him. It was a cold day. I’ll

never forget it. I didn’t have any gloves, I didn’t have

a hat or scarf or anything. I was sitting on the back of that motorcycle,

and we were going out to[the air field. I was so cold, so I got somebody

to take me home in their car, and he got so mad at me. I’ll

never forget that.

Johnson:

That’s quite a story.

Jaehnig:

Jack [John P.] Reeder was a test pilot. I knew him. I taught all of

his children in school. I got situated not working at NACA anymore,

and I taught school. I loved teaching school. I adored it. I could

do it all over again if they’d have me. That was my thing. I

taught math, music, and art.

Johnson:

What a combination!

Jaehnig:

Yes, it was wonderful.

Johnson:

How many years did you teach?

Jaehnig:

Almost 20, and I loved every minute. I absolutely adored it. I was

made to teach. I was. I think my experience of working in the field

like I did made a big difference, because I taught a lot of children

that wanted to go into that field. They didn’t get any encouragement

from anybody, but they got it from me. I think that helped a whole

lot, because I had experienced it, and they could see how much I loved

it, and I loved teaching. I just adored teaching, because I like children.

I taught in the neighborhood school, so no busing. [Many] walked to

school. They would go home after school, change their clothes, and

come back to school. They would come back in my room, and they would

say, “Mrs. Jaehnig, will you come out and play with us?”

I said, “Of course. What do you want to play?” So, I’d

go out on the playground and play with them. It was wonderful.

Johnson:

What grades did you teach?

Jaehnig:

Six and seven—the hardest ones. It’s the hardest age,

but I adored it. I adored it. I could handle them. I could give them

a dose of their own medicine. I did not have a single discipline problem.

I really didn’t. I just loved every minute of it. Just every

minute of it—I loved it. I’d go back tomorrow if they’d

have me.

Johnson:

When you first got to Langley, were there a lot of social activities?

It was during the war, so was everyone just concentrating on the work,

or did they also have the social activities?

Jaehnig:

No, they had parties. There was a lot of drinking, which I didn’t

get involved in. There was a lot of drinking and all that kind of

stuff. These people were just out of school, and they were really

spreading their wings. That didn’t make me happy. That didn’t

make me happy at all. I wasn’t that type of person. There was

a lot of drinking and all that, but I never got involved in all that,

but it was there.

Johnson:

How did you meet your husband?

Jaehnig:

He lived in the apartment next door to me. He was the only one that

had a car, so we all went for him. He inherited a car from his grandfather.

It was a Studebaker. It was a nice car, too. He did a lot of hauling

around of people. He was very popular.

Johnson:

I imagine, during that time, because it was hard to get a car during

the war.

Jaehnig:

It was. We had that Studebaker for a long time after we were married.

Having a car was really something.

Johnson:

That was an interesting time. Rebecca, do you have any questions?

Wright:

You mentioned earlier when we were chatting that he went to war as

well?

Johnson:

He joined the service [U.S. Public Health Service – “declared

to be a military service and a branch of the land and naval forces

of the United States” during WWII].

Jaehnig:

Yes. He knew that he was going to be drafted. That was when they had

the draft. He knew that his name was going to come up soon, so he

went ahead and joined.

Wright:

Did you work while he was gone, or were you home?

Jaehnig:

I quit working when I got married, because I didn’t have a job,

and he was stationed in Mississippi. They were so backward. Oh, golly!

I had a job in Mississippi, but it was nothing to do with aeronautics.

I had a job as a classification agent for a cotton bale company. That

was the only job you could have. We didn’t have mayonnaise.

We didn’t have any shoes. They were all rationed. All of the

shoes were made out of cardboard. We couldn’t get salad dressing.

We couldn’t get butter. We couldn’t get anything like

that, because they were using all of the grease for ammunition, so

therefore, we did without a lot of stuff. That didn’t make any

difference to us. We didn’t care. He joined the Public Health

Service, even though he was not that trained. He did research work

for malaria fever. That’s what he was put in.

Johnson:

He was a civil engineer, doing research work on malaria. How interesting!

Jaehnig:

He got malaria. He did. Yes, he caught malaria. I never will forget

it. I thought he’d never get well, but he got it from fooling

around with doing experiments with mosquitoes. That’s what they

put him on. That’s the way that the government does though.

Johnson:

I guess so.

Jaehnig:

He stayed just long enough after the war was over, he got out. His

former professor offered him a job teaching at the University of Wisconsin.

He taught surveying. That’s the way it was.

Johnson:

When did you come back here?

Jaehnig:

We came back here when it got so cold I couldn’t take it anymore.

You go outside, and it’s 20 [degrees] below every night. You

wash a diaper, and it freezes before you can put it on the line. It

was stiff as a board before you put it on the line. I had to walk

as far as from here to the highway to go to the bathroom, but I was

happy. I was happy. I was not unhappy a bit.

I can remember one night. We heard this sniffling in our tent. I quickly

got up. He said, “Do you have anything to eat in here?”

I said, “Yeah, I’ve got a candy bar.”

He said, “Give it to him.” It was a raccoon. So, I got

my candy bar and gave it to that dumb raccoon. We were lucky. We had

a floor in our tent, but the top was canvas, and all of these daddy

longlegs crawling everywhere. I’ll never forget them. It was

hard.

Johnson:

But, you made it through.

Jaehnig:

We were happy. You learned to be happy, I don’t care what your

situation is. You learned to be happy, and so it didn’t matter

to us. You’d just adjust.

Johnson:

You started teaching when you came back here? Is that when you started,

after you had your children?

Jaehnig:

Yes, after my children, I decided I was not going to teach until my

children were big enough to come home, and if I’m not there,

they’d be okay. They were in the fourth and eighth grades before

I started teaching. It was the right thing for me. I loved teaching.

I’d go back tomorrow if they’d have me. I really loved

teaching.

Johnson:

Is there anything we haven’t talked about that you’d like

to talk about, or any other experiences, anecdotes, or anything you

want to share during your time there?

Jaehnig:

I’ll think of a million things tonight. I hope I haven’t

disappointed you.

Johnson:

No, not at all. You’ve told us some things that are pretty interesting.

Wright:

Crawling up in those planes. Did they ever take you on a plane trip?

Did you ever get to ride in one of those planes?

Jaehnig:

No. They never took me up. I guess they were afraid I’d jump

out!

Wright:

That wouldn’t have been good.

Johnson:

Thank you so much.

[End

of interview]

Figure

1 - Human Computers; Women at NACA and early NASA. Typical computing

area.

Photograph from “Human Computers” - NASA Cultural Resources

(CRGIS)

http://crgis.ndc.nasa.gov/historic/Human_Computers

Figure 2 – Excerpts from:

National

Advisory Committee for Aeronautics Technical Note 2194

The NACA Oil-Damped V-G Recorder, by Israel Taback (October 1950)

The

effect of atmospheric turbulence on the loads encountered by aircraft

in routine operational flight has for some time been studied by analyzing

the records secured with the NACA V-G (velocity-gravity) recorder.

The

original NACA V-G recorder in which the accelerometer unit was damped

by dry friction could give satisfactory results when damped and installed

in a proper manner. Acceptable records were secured if the accelerometer

damping unit was adjusted correctly in each particular application.

This adjustment, however, was difficult because of the requirement

that the adjustment be made in the field by relatively inexperienced

personnel and because changes in damping occurred with time and operating

conditions.

Installation

The

instrument may be attached to any accessible rigid part of the airplane

structure at a location as free from engine vibration and as near

the center of gravity of the airplane as possible.

Loading

(1)

Remove the circular cover above the name plate by releasing the spring

hold-down lever. In order to loosen the cover plate, it maybe necessary

to insert a knife blade or screw driver under the pins in the cover

plate and to pry gently until it is free of the instrument case.

(2)

Use tongs or a pair of pliers to grip the edges of a glass record

plate and apply a thin film of lampblack to one side of the plate

by passing the glass back and forth over a small, slightly sooty oil

or candle flame. With a little practice, a uniform film of proper

density can be applied.

(3)

Place the glass in the retaining grooves on the back of the cover

plate, push in to the pin stop, and replace the cover plate in the

instrument.

Handling

of Records

Flight

records should be carefully removed from the cover plate to avoid

rubbing off any of the smoke film. The record should be placed on

a slight incline and a few drops of the thin fixing lacquer supplied

with the recorder should be applied with a medicine dropper to the

upper edge of the record glass. Allow the lacquer to flow over the

smoke film and dry of its own accord. If a sufficient amount of this

lacquer is applied along the upper edge of the glass, the whole surface

will be covered uniformly. Identification of each record should be

scratched on the unused part of the smoke film.

Figure

2(a) – V-G Recorder – Front (above) Cover Removed (below)

NACA TN 2194

Figure 3 – Langley Tow Tanks

Tow

Tanks (Building 720) Test Apparatus; 1945

http://crgis.ndc.nasa.gov/historic/File:L-43585.jpg

B-29 Ditching Test, Tow Tanks Building 720; 1946

http://crgis.ndc.nasa.gov/historic/File:1946_B-29_Ditching_Test.jpg

Excerpt from: Legacy in Safety: NASA Contributions to Knowledge

in Aircraft Ditching

http://crgis.ndc.nasa.gov/crgis/images/8/85/2009Ditching.pdf

During

World War II, a major operational problem arose for the nation’s

military aircraft and the focus of research in Langley’s towing

tanks was redirected. The problem of ditching, defined as the forced

landing of a land-based airplane at sea, had become a critical issue

for aircraft in the European and Pacific theaters. Damaged and fuel-starved

aircraft were being routinely forced to ditch at sea, and many designs

lacked adequate structural design and optimized procedures for surviving

the impact of the landing. In addition to structural failure and excessive

(often fatal) loads transmitted to the aircrews, some aircraft rapidly

nosed over into a deep dive, completely submersing the crew and preventing

escape.

In

1943 the Army and Navy requested that Langley undertake a major study

of ditching with a view to providing procedural recommendations to

operational military units as well as to provide designers of new

military aircraft with valuable data. The resulting research effort

at Langley was extremely broad, including: structural tests to determine

the structural load limits of actual aircraft such as the Boeing B-17

Flying Fortress, the Consolidated B-24 Liberator, and the Martin B-26

Marauder; measurement of the stresses imposed on structures during

landings in calm and rough seas; and observations of aircraft behavior

during ditching as replicated by free-flight models in Tow Tank 2.

Virtually

every U.S. bomber and fighter configuration was evaluated in simulated

ditching tests to determine the most desirable airplane attitude and

configuration for ditching. Major questions required answers, such

as whether to deflect wing trailing-edge flaps or extend the landing

gear, whether bomb-bay doors should be opened to partially absorb

the impact, and whether one wing tip should be allowed to hit the

water first to slew the airplane around to absorb energy.

Figure

4 – Early “Calculators” Used by Women Computers

(photographs from “The Museum of HP Calculators”)

http://www.hpmuseum.org/srbig.htm

Monroe

Friden